- Home

- Ron Jaworski

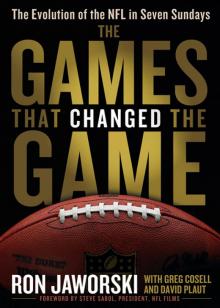

The Games That Changed the Game Page 11

The Games That Changed the Game Read online

Page 11

During our Super Bowl season of 1980, the Eagles flew to San Diego to play the Chargers. It was the first time I got the chance to see the “Air Coryell” offense in person. They beat us that day to snap our eight-game winning streak, but that’s not what I remember most about the game. It was one of the few times in my career when I didn’t just sit on the bench and collect my thoughts while our defense was on the field. I made it a point to study Fouts and the rest of Air Coryell. They were so much fun to watch—even if they were having fun at our expense. For sheer beauty of timing and rhythm in the passing game, that Chargers team is still the best I’ve ever seen.

I believe Coryell owes a great deal of his success in San Diego to Bud Carson’s famed Steel Curtain defense. Its dominance mandated the introduction of the illegal chuck, or Mel Blount, rule, and liberalized offensive line blocking regulations. These major changes became part of the game in 1978, right at the time Coryell was hired by the Chargers. Don may not have been the first to take advantage of these new rules, but he was the best at taking advantage of them.

Several of Don’s philosophies can be traced directly to Sid Gillman: forcing opponents to defend the entire field, emphasizing quarterback pocket protection, and relying on timing and rhythm in the passing game. But then Coryell went a step further. Those liberalized 1978 rules created the perfect climate in which to implement previously unseen formation shifts and men in motion. If defenders were allowed contact only near the line of scrimmage, why not have receivers moving prior to the snap, where they’d be almost impossible to jam? And why limit this to wideouts? Why not running backs or the tight end as well? Motion produced another benefit: If a defensive back or linebacker rotated with the moving player during pre-snap, this was a good indication that the defense was in man-to-man coverage. For a sharp quarterback like Fouts, knowing this even before the play began was a tremendous advantage.

Coryell and his longtime assistant Ernie Zampese looked to force opponents into default, or base, coverages—vanilla defenses they knew how to beat based on film study. So while opposing defenses made themselves predictable, Coryell’s offense was anything but. He ingeniously created a system of routes that relied on formation and alignment, not on the receivers themselves. On a given pass play, all five receivers could set up shop anywhere in the formation. If that wasn’t enough of a defensive headache, he made it worse by having Fouts pass the ball before the receiver even made his break. How can a defensive back cover his man when the throw is to a spot the pass target isn’t even looking at? All these elements made Air Coryell varied, unpredictable, and just about impossible to defend. At least those problems existed only against the Chargers, because nobody else was doing this at the time. Ask former Raiders and Bills linebacker Phil Villapiano about defending against the Chargers, and he simply shakes his head. “They’d run you into the ground,” he said. “Coryell would have five receivers that were potential targets on every down, and you can’t cover five receivers. It’s amazing how Fouts was coached to find the open guy all the time—and believe me, someone was always open.”

Nobody else had a tight end like Kellen Winslow, either. Hall of Famers like John Mackey and Mike Ditka were rampaging bulls who could bowl people over after the catch. So could Winslow, but his skills went far beyond brute strength. Kellen was a superb route runner with great hands—practically an oversized wide receiver. There were other tight ends of this period that might also have done well in Coryell’s system: Dave Casper, in his days with the Raiders, and Cleveland’s Ozzie Newsome being two who come to mind. But they played for other teams that didn’t use the tight end (or the “Y,” as the position is called in playbook parlance) the way the Chargers did.

Coryell and Zampese set Winslow up anywhere on the field. They put him in motion where he couldn’t be jammed. They’d line him up in the slot or out wide against some unfortunate five-foot-eleven, 180-pound corner. How on earth can that guy defend a six-foot-five, 250-pound receiver who runs just as fast as he does? That is the classic mismatch NFL coaches dream about—and in San Diego, mismatches like this existed on every play

Winslow wasn’t his quarterback’s only choice. There was Hall of Famer Charlie Joiner, who ran the most precise routes of any receiver in that era. And there was John Jefferson, who was as athletically gifted as any target on the Chargers. J.J. could stretch out and grab anything—even overthrows. The Chargers could also run the rock with 245-pound monster Chuck Muncie. You can see why opposing defensive coordinators probably lost a lot of sleep preparing for San Diego.

As I’ve said many times, if you control the middle of the field, you control the game. It was Gillman’s mantra, and it became Coryell’s too. The quickest way to the goal line is a straight line, so when you send a target like Winslow down the middle, the safeties must stay home and play honest. And if you then add threats on both outside flanks the way the Chargers could, you put enormous pressure on every defender. This creates advantageous one-on-one matchups, and against a team of talented athletes like the Chargers, that was usually enough to get beat.

Beyond being a brilliant tactician, Coryell was adored by his players, and his teams were a joy to watch. “The most important thing to me about Don Coryell is him as a person,” said Fouts. “He actually cared about us as players. A lot of coaches don’t even know who you are. They call you by your number. But Don was always a guy who made you feel important, who made you feel that your contributions to the meetings, or the team, or to the locker room was part of the deal, and we were all in this together.”

on Coryell had already enjoyed a lifetime of experiences by the time he arrived on the campus of San Diego State College in 1961. He’d served in both ski and paratroop divisions during World War II, later worked as a lumberjack, then played defensive back and competed as a boxer at the University of Washington. He coached junior college football before taking on the head coach’s position at Whittier College from 1957 through 1959. After a year as John McKay’s running-back coach at the University of Southern California, Coryell was brought in to revive the Aztecs’ struggling football program.

His first hire was Riverside City College assistant Tom Bass, who would run the defense. “I asked him why he wanted to go to San Diego State, because they hadn’t won a game in three years! He told me he thought that he could do a lot better than that,” said Bass. “Joe Gibbs was a player for us then—he was our tight end and also played linebacker. He also filled in one game at center when our regular guy was injured. We only recruited junior college players, and Joe was one of them. We never even talked to high school kids. We only had thirty-three scholarships back then. It just seemed easier for us this way. Don and I did all the recruiting. It took some of the guesswork out of player evaluation. Everyone we brought in was ready to play.”

San Diego State was an independent in those days, which meant that it wasn’t tied to specific conference regulations dealing with player transfers or eligibility. “A lot of kids who were recruited by the big West Coast powers got to these colleges and realized they couldn’t cut it there, for a number of reasons,” remembered Al Saunders, who coached for Coryell with both the Aztecs and Chargers. “Don got lots of players this way, especially receivers. Because of the loose rules, he could get a kid to enroll at San Diego on Wednesday and then play them that Saturday. So Don had to devise an offense where he could get guys in and have them ready to go in just a few days. He devised a three-digit numbering system in his passing tree and could teach a kid the basics of that system in five minutes. Naturally, the player wouldn’t know all the route combinations and adjustments, but everybody can count from one to nine.”

Gibbs, whom Coryell recruited as a junior college player, said of his mentor, “The way he arrived at the three-digit system and his way of calling the passing game was one of the more enlightening things that has ever been done in football. The system basically was: The higher the number, the deeper the route. Inside cuts were even numbers, outside cuts were

odd. That was easy to remember. On the first day Don coached a receiver, that guy could learn basic plays. The idea behind it all was to give the quarterback a visual picture.”

San Diego State didn’t become a passing powerhouse right away. “At first we were an I-formation team because Don had coached that with McKay at Southern Cal,” said Bass. “But by year three, we were throwing the ball a lot more. We really started passing more when Rod Dowhower was our quarterback, and then Don Horn, who was eventually drafted number one by the Packers. Coryell wasn’t wed to anything. He saw that passing would help us win. He understood that we could get national recognition—not just by winning but by scoring a lot of points, and the only way to really do that was to throw the ball.”

Being in San Diego at the same time as Sid Gillman had little impact on Coryell. “Don didn’t spend as much time at the Chargers’ camp as I did,” Bass added. “He really was his own innovator. He just watched a lot of football and picked up ideas that way. He also attended a ton of clinics. In those days, you practically lived at them. Don had total and complete tunnel vision during football season. I remember the two of us taking a recruiting trip up to Bakersfield. I did the driving, Don was sitting next to me, and it was two hours before he said a word. The whole time, he was drawing plays on index cards, then throwing them in the back seat. He must have gone through about two hundred of those things. But that was just Don—he was so totally focused. He really had no hobbies or outside interests, other than his family.”

In 1964 Bass was hired by Sid Gillman to be the Chargers’ back-field coach, but Tom wasn’t going to leave Coryell empty-handed. He recommended a young junior college coach named John Madden, who would serve as Coryell’s defensive coordinator for three years. “John knew Ernie Zampese from Santa Maria Junior College,” Bass recalled, “and after Madden came to San Diego State, he got Ernie to join the staff as well. Ernie knew Coryell from USC, where he’d played as a defensive back. Ernie was a lot like Don in that he had no ego. He never wanted to be a head coach, wasn’t big about working on his own—he most enjoyed working with Coryell. Having played defense in college really helped Ernie when he coached the offense at San Diego State and then the pros.”

By the late sixties, the Aztecs’ passing attack had grown quite sophisticated. Receivers Gary Garrison, Haven Moses, and Isaac Curtis all excelled in Coryell’s system before going on to the NFL. The succession of passers after Don Horn included Dennis Shaw, Brian Sipe, and Jesse Freitas—all eventual NFL quarterbacks. According to Bass, “When Sipe first got to Cleveland, he realized the stuff he was doing with Coryell at San Diego State was way ahead of what the Browns were doing.”

Coryell had other NFL admirers just up the coast in Los Angeles as well. “Don was always ahead of his time,” claimed Dick Vermeil. “When he coached at San Diego State, I used to go down there as a Rams assistant, watch them practice, steal stuff from them, and then put it in our Ram offense.”

The Aztecs hardly ever lost with Coryell in charge. During his dozen years at the school, Don posted an astounding record of 104-19-2. At the end of the ‘72 season, he was hired by the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals to do the same thing he had done in San Diego: revive a moribund football team. Within a year, Coryell took the Cardinals to a division title and their first playoff appearance since 1948. He succeeded for two more seasons by utilizing the same formula that had worked for him in college: putting the ball in the air early and often. “Don would always be yelling, ‘Throw it, throw it!’ “ recalled Cardinals quarterback Jim Hart. “It could be third-and-inches, and he’d come to our huddle during a time-out and tell us to throw it. He loved throwing on every down.”

Hart recalled other ways that Coryell displayed his competitive and often combative nature. “We were playing the Eagles, staying at a hotel in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and the bus driver wouldn’t pull into the entrance because he said it was too tight a space for him to get in. Don got mad and said, ‘My players aren’t going to walk a hundred yards through snow because of you.’ He was ready to duke it out! The driver asked him if he wanted to step outside, and Don said, ‘You bet I do!’ And this was the day before a game!”

When it came to interacting with his players, however, Coryell shunned the tough-guy approach. “I have no interest in intimidating people,” he said. “I’d rather help people. I treat a player the way I’d want to be treated, try to help him become a better player by giving him an opportunity to do the things he can do best. I don’t think a coach has to be a son of a bitch to be successful. I think you can treat men like men.”

For Coryell, it was all about looking after his athletes, even if it sometimes put him at personal risk. Hall of Fame tackle and current broadcaster Dan Dierdorf has his own favorite story about Don’s dedication: “We’d just gotten a defensive tackle from Pittsburgh named Charlie Davis, and in his first day of practice, he got in a fight with Conrad Dobler. I don’t know what Coryell could have possibly been thinking, because Don’s a little guy. He jumped in between these two huge linemen to try and break it up. And Charlie goes with this big roundhouse right, Conrad ducks, and Coryell gets struck right on the bridge of his nose. Blood is spurting everywhere, and the trainer runs out to try to help Don, but he waves him off. He stayed out there and just continued to run practice like nothing had happened.”

That same focus and intensity carried over into Don’s daily life. “Don lived in a rural area about an hour outside of downtown St. Louis,” Hart remembered. “I heard a story where he’d put his garbage in his car so he could stop and deposit it somewhere right outside his house. I think he dropped his daughter off at school and then just continued on downtown, so consumed with football that he completely forgot he had all that trash in the back of his car.”

What occupied Don’s mind the bulk of the time were his thoughts on how to improve the Cardinals’ explosive offense. He was always looking for new ways to exploit such stars as running back Terry Metcalf, receiver Mel Gray, and tight end Jackie Smith. But the creative innovations he’d eventually dream up with the Chargers were still a few years away. “There was nothing of what we know of as Air Coryell in St. Louis,” claimed Gibbs, who served as an assistant on both the Cardinals’ and the Chargers’ coaching staffs. “His scheme in St. Louis was totally different. It was different personnel, different sets, more of the standard split backs. We had a very gifted quarterback in Hart, and Don certainly wanted to throw the football. But we were not in the one-back set. We ran standard formations. The tight ends ran conventional routes. We wanted to be balanced, and it helped having a great offensive line with Tom Banks, Bob Young, Dierdorf, and Dobler.”

In the final month of the ‘77 season, the Cardinals fell apart, dropping their last four games, including a loss to a Tampa Bay Buccaneers team considered to be the worst in the league. St. Louis finished at 7-7 and management abruptly decided to make a coaching change. But Don wasn’t unemployed for long. After the Chargers dropped three of their first four games to open the ‘78 schedule, they accepted head coach Tommy Prothro’s resignation and brought Coryell in as his replacement.

It was too far into the season to install his entire offense, so Coryell made a gradual shift by adding selected plays to the Chargers’ repertoire. Even so, San Diego won eight of its last nine games, and the team entered the ‘79 season brimming with confidence. The players were especially excited about the revamped offense put together by Coryell, Gibbs, and Zampese, an attack with roots in another San Diego coach from the past. “Dating back to Sid Gillman, most teams used the passing tree,” recalled Chargers running back and specialteams captain Hank Bauer. “It’s a numerical system tied into the number of steps of the quarterback’s drop. Shorter routes are small numbers. Even numbers are inside routes. Odd numbers are outside routes. The deeper the quarterback’s drop, the longer the receiver’s route.”

Sometimes those routes were deep enough to score long touchdowns. “The first thing in our offense was always the bomb

,” stated Fouts. “It was built into almost every pass play, where the quarterback initially looks for that chance to hit the big one. And I think if you start with this premise and then work your way back toward the line of scrimmage, that’s the Air Coryell offense.”

When Coryell began varying offensive formations, Fouts could get pre-snap reads because of the way the defense reacted. “Dan would know probably ninety-nine percent of the time what coverage he faced before taking his drop,” said Bauer. “It’s much harder to read coverage after the snap when the pass rush is coming and you can’t see. As soon as Dan confirmed that coverage, that ball was out of his hand. That’s what made it so lethal. If the ball’s in the air before the receiver comes out of his break, there’s absolutely no way a defensive back—unless he guesses—can make the play. And at that time, nobody in the league had seen that.”

The timing of the offense didn’t fall just on the quarterback. The line and everyone else had to work together. The launch point, the breaking points, the landmarks on the field—all had to be consistent. If you were supposed to break at 10 yards with your inside foot, you’d better do it just that way. Not 12 with your outside foot, because that wouldn’t work. And you had to have the right mind-set to accept that style of coaching: factors such as the depth of the quarterback drops and where the ball was going. The system demanded precision, and coaching it required a lot of repetition.

Let me walk you through a typical play progression to better illustrate the concept. Say that Charlie Joiner is split outside, and there’s a corner playing on him. If the corner’s playing inside technique, he’s in man-to-man coverage. But on which side is Charlie coming out of his break? He’ll break it to the outside, because what’s the point of coming back to the inside when the defender is sitting there waiting for him and can play the ball? If Joiner pushes him, then breaks outside, it’s almost impossible for the defender to make the play.

The Games That Changed the Game

The Games That Changed the Game